Abstract art uses colors, shapes, and lines to create compositions that are independent from references in the real world. The history of abstract art dates back to the birth of Cubism and Fauvism. Alfred H. Barr Jr. distinguished two main trends in abstract art in his book Cubism and Abstract Art: the geometrical, structural current as it developed in Cubism and later in Constructivism and Mondrian, and the intuitional, decorative current through Kandinsky and later Surrealism [1]. As a pioneer of Suprematism, which originated from the Russian avant-garde movement along with Constructivism, Kazimir Malevich’s artwork should be listed in the first category; however, he aims to use his creations to lead people to discover things beyond cognition, which could be shown especially in his oil painting Black Square. This goal has some coincidence with Kandinsky’s attempt to connect the audience with pure, abstract music. In this essay, the author will use specific artworks to analyze the differences and similarities between Kandinsky and Malevich’s artistic attempts to achieve abstraction.

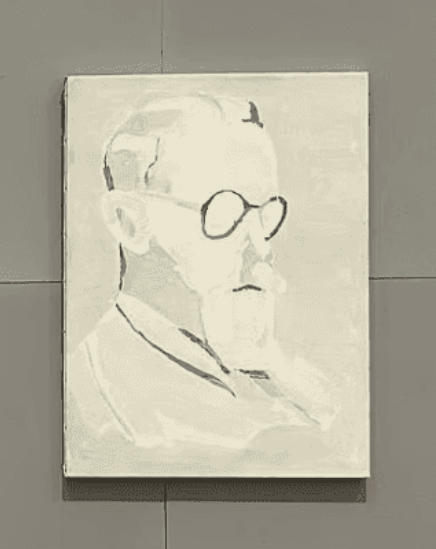

Being inspired by the epic tenth-century tale by Wagner, the composer who raised the idea of Gesamtkunstwerk, Wassily Kandinsky aims to create music within his artwork. According to him, he had sensed the colors expanding in front of his eyes when he was listening to Wagner’s music[2]. Later, he devoted himself to painting a series of Improvisation pictures. He aimed to create a visual soundscape that enabled the audience to hear the “inner sound” of color. Kandinsky believes that our soul is suppressed by the reign of materialism, and modern art, as the art form that is produced in the particularly modern age, would be a way to help people turn to their true inner self and be released from the unrealized suppression [3]. Kandinsky believes colors inside the painting could bring the audience a special spiritual effect. The audience will generally have two effects. First, the eye would be charmed by the beauty and other qualities of the color. Although the psychic experience is superficial, it could develop into a deeper form of experience, and here comes the connection between painting and music [4]. Kandinsky believes: “The constantly growing awareness of the qualities of different objects[in the painting] and beings is only possible given a high level of development in the individual. With further development, these objects and beings take on an inner value, eventually an inner sound.[5]”At the second step, the color would strike psychological effect and make the colors reach the soul. “In general, therefore, color is a means of exerting a direct influence upon the soul. Color is the keyboard. The eye is the hammer. The soul is the piano, with its many strings.[6]”

The Improvisation series includes Kandinsky’s visual creations of the painting. He used random, relaxing lines and color blocks to depict his understanding of music pieces, hoping the audience could understand. In Improvisation VII, Kandinsky filled the canvas with colors and lines. The artwork was completely abstract, without any reference to real life. However, under the complete chaos, people could sense the rhythm underlying its surface: the place where shapes and lines accumulate forms a swirl, growing from the right side of the canvas; the space beside the swirl is filled with colors, too, but shallow and blurry, creating a sense of space. At the left side, it seems like the shapes and lines are flooding out of the swirl-like sack and fading into the fog at the left end. An abundance of colors is displayed on the canvas, like the ambitious members going on a vigorous campaign, but each following an unspoken order without crowding together. The audience would feel the huge noise emanating from the canvas without hearing any actual sound. Kandinsky imagined the audience’s potential reaction: the bright lemon yellow hurts the eye, just like how a high note on the trumpet hurts the ear[7].

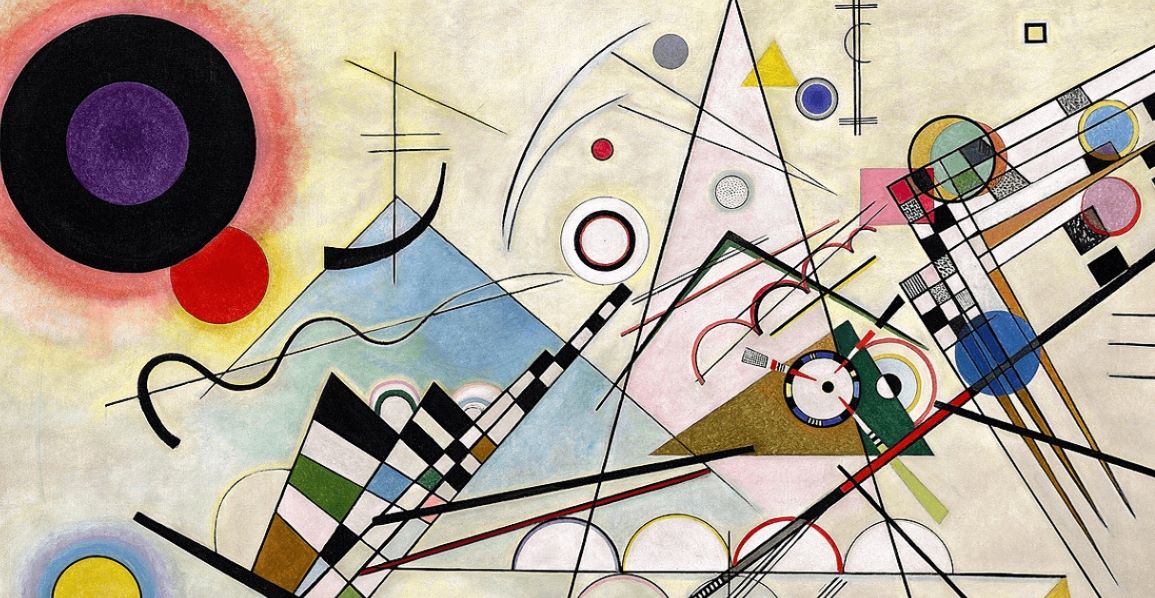

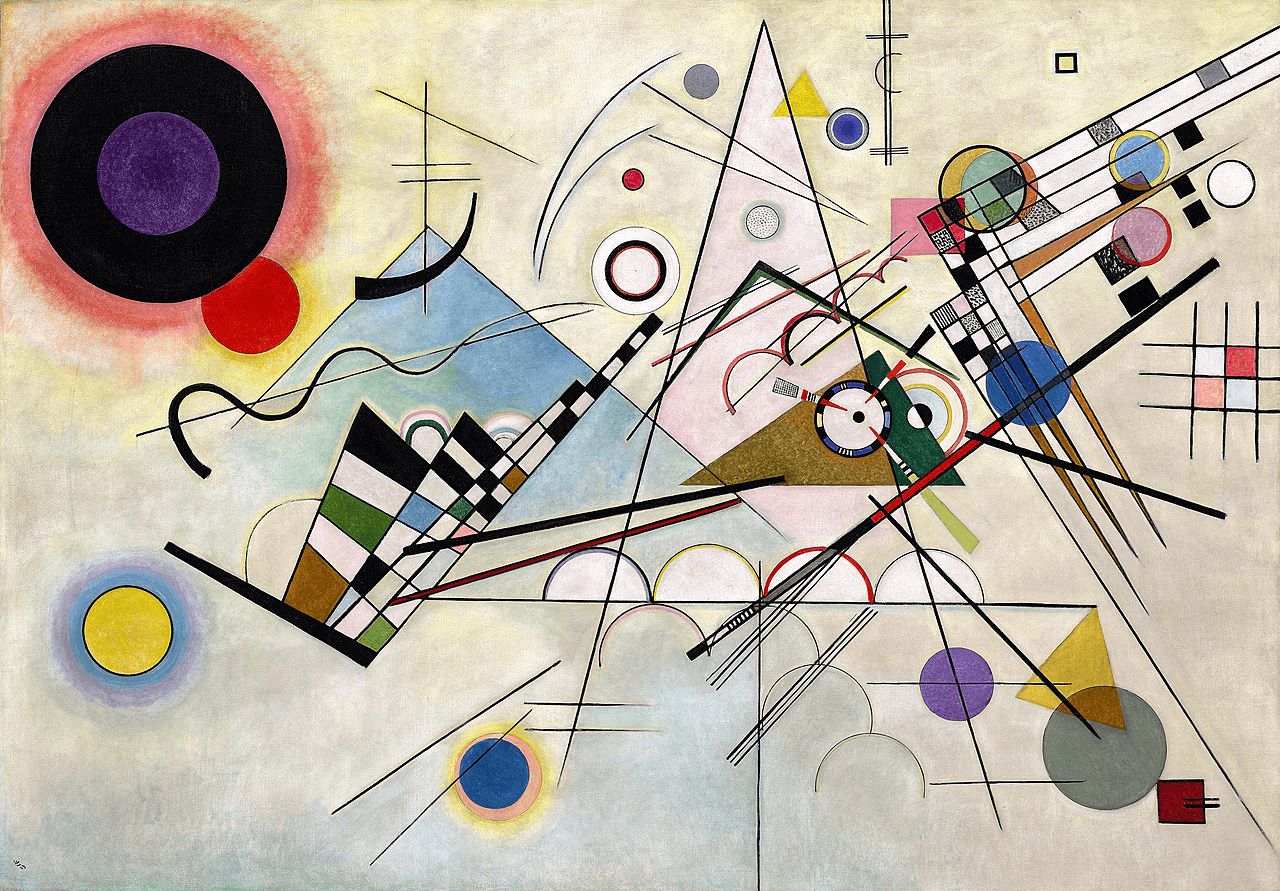

When Kandinsky returned to Moscow after WWI, his style underwent changes showing the influence of Russian avant-garde artists. Being influenced by Suprematism and Constructivism, he included more aspects of the geometrizing trend in his artworks. Later, in Bauhaus, he furthered his investigation of colors and forms with the Composition series. In Composition 8, straight, thin lines and regular geometric shapes dominated the canvas. Several circles that could only be made by the bow compass were scattered to different places on the canvas. Kandinsky himself believes the importance of circles in this painting prefigures the dominant role they would play in many of his subsequent pictures. “The circle is the synthesis of the greatest oppositions. It combines the concentric and the eccentric in a single form and in equilibrium. Of the three primary forms, it points most clearly to the fourth dimension.”[8]Whether the audience could understand his effort or not, his pursuit of total abstraction has come to a milestone. The audience’s natural inclination to decipher the content in any way is thwarted by his shapes and lines, prompting them to turn inward for reflection.

After a few years of Kandinsky declaring his artistic pursuit, Malevich announced the establishment of Suprematism. The aim of Kazimir Malevich’s composition could be summarized with the first sentence of his manifesto From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism: The New Realism in Painting: “Only with the disappearance of a habit of mind which sees in pictures little corners of nature, madonnas and shameless Venuses, shall we witness a work of pure, living art.[9]” To achieve his goal, he chose to eliminate all visual elements that refer to objects in real life.

According to Malevich, the first attempt at art laid the basis for conscious imitation of nature. The artist of collective art, the art of copying, has only developed his art on the side of nature’s creation, not the side of new art. He believed such a concept of art is false. The modern movements “cast off the robes of the past and came out into contemporary life to find a new beauty”. He firmly pointed out: artists become creators only when forms in their work have nothing in common with nature. colors and texture are ends in themselves, and their essence is always destroyed by the subject[10]. In Futurist paintings, faces are painted green or red. But only when the faces painted green and red to an extent that kills the subject could the painting live [11]. Thus, pure colors and shapes became his artistic expression.

His seemingly most extreme attempt, also the first attempt of Suprematism, Black Square, illustrates how he reduced everything to nothing[12]. The design was created as the background design in a Futurist opera, Victory over the Sun. However, Malevich gradually discovered the importance and meaning of this abstract black square, so he created the artwork Black Square in 1915 as the manifesto of Suprematism [13]. The content of the painting was simple: a black square at the very center of a white square canvas. However, Malevich’s intuition is not: He wanted the audience to focus on the form of the black square, think about the relationship between white and black color, enjoy the texture of color, and even feel a sense of movement in this absolutely motionless painting[14]. He assumed that when people look at the square, even though no inference to the real world is shown on the artwork, the audience would still try to interpret the artwork, and their subconsciousness could take place during this mentally wandering journey[15].

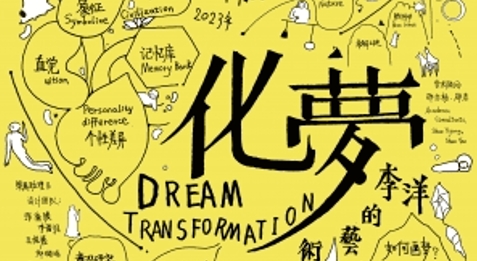

However, the development of Suprematism didn’t come to an end after Malevich’s pure color creations. His painting Suprematism in 1915 was another attempt of pure art, but this time, the canvas is filled with shapes with different colors. The black, irregular shape that is consisted of several rectangles lied in the middle. A thin, straight line run across the black shape, stretching to the upper left corner and the lower right part of the canvas. Plenty of shapes are laying on the line. Rectangles crisscross each other in an irregular way. Irregular, random rectangle clusters are placed at the lower left and right corners, also some places at the left side and the right side. Shapes with curves are few, scattering in some places on the canvas. Clearly, the artist is not conveying any message through the shapes. There are pure shapes and colors, pointing to the nonobjective world, leading the audience to the ultimate artistic journey. The constructions that comprise the composition of the picture personify the artist’s concept of the universe. Since the artwork does not have a top or bottom, the artist creates a new reality on his canvas [16]. In this painting, Malevich led another spiritual journey through colors. He uses the colors to create an imaginative space, but the space itself could only be created inside the audience’s heart. Again, the colors and textures became “ends in themselves”[17].

From the analysis above, we could roughly conclude their difference and similarities in their artistic pursuit. Kandinsky wanted the audience to use different senses to appreciate his work. Malevich required the audience to wander in his pure colors using subconsciousness, rather reaction towards visual stimulation. While Kandinsky turned to another art form relating to abstraction, Malevich delved into the abstraction within visual art itself. However, both attempts aimed to lead an inner way of perceiving beyond pure visual perception. Kandinsky attempted to evoke different senses through art that could only be directly perceived by vision. Malevich stepped further, giving up all sensual perception, and turned to pure mental experience. Besides, both artists highly require the in-depth interaction between the audience and the painting. In their imagination, the audience would keep trying to wander inside the artwork, until their inner sense function without even knowing it.

[1] Taylor & Francis Group, abstract from Alfred H. Barr, Jr. Cubism and Abstract Art, https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9780429059148/cubism-abstract-art-alfred-barr-jr

[2] Will Gompertz, 150 Years of Modern Art in the Blink of an Eye, USA: Penguin Group, 2013, p.655

[3] Wassily Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art Theory 1900-2000, ed. Harrison & Wood, 2003, originally written in 1912, p.83

[4] Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual, 87

[5] Ibid., 88

[6] Ibid., 89

[7] Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual, 88

[8] Wassily Kandinsky Composition 8(Komposition 8), Guggenheim Museum, https://www.guggenheim.org/artwork/1924

[9] Kasimir Malevich, From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism: The New Realism in Painting in Art Theory 1900-2000, ed. Harrison & Wood, 2003, originally written in 1916, p.173

[10] Malevich, From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism: The New Realism in Painting, p.174-175

[11] Malevich, From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism: The New Realism in Painting, p.179

[12] Will Gompertz, 150 Years of Modern Art in the Blink of an Eye, USA: Penguin Group, 2013, p.517

[13] Gompertz, 2013, p.514-517

[14] Gompertz, 2013, 518

[15] Ibid., 520-521

[16] The State Russian Museum, Suprematism, Google Arts & Culture, https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/suprematism/7gFr9friECE5NA , accessed June 3, 2025

[17] Malevich, From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism: The New Realism in Painting, 175